When Success Sours (Stanford)

CAROL DWECK’S RESEARCH has made the Stanford psychologist a household name among parents and teachers. Since the 2006 publication of her book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success(and Stanford’s March/April 2007 cover story), countless articles and books have featured her ideas about helping children and adults learn. The video of Dweck’s 2014 TEDx talk on “growth mindset”—the power of believing that you can improve your abilities and talents—has been viewed more than 4.7 million times. And U.S. sales of Mindsetrun from 7,000 to 14,000 copies weekly, according to her literary agent, suggesting wide-ranging popularity.

But Dweck’s stardom has come with a harsh side effect: In the minds of many, “growth mindset” mutated almost beyond recognition. As she recently put it in her characteristically delicate way, “I slowly became aware that not all educators understood the concept fully.” As a result, Dweck has been reaching out to educational audiences in person and in print to dispel some troubling myths.

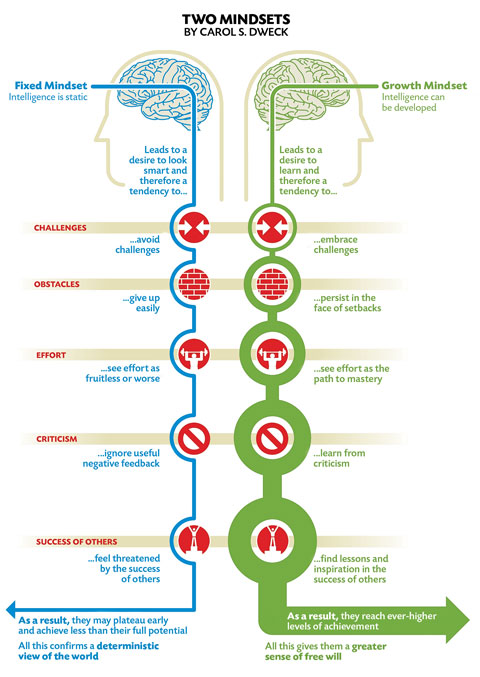

At its core, the concept doesn’t seem hard to understand. In decades of experiments, Dweck and colleagues have often pitted a growth mindset against its opposite, the belief that ability is a fixed trait. In one series of studies, children who were praised for their intelligence developed a fixed mindset; their goals shifted from learning to showing how smart they were. They chalked up failures to low intelligence, giving up more quickly and performing worse than peers who’d been praised instead for hard work. (See chart below.)

Unfortunately, many of Dweck’s acolytes came to equate a growth mindset only with effort—as if students’ hard work alone, without effective instruction from teachers, could help them master whatever skills they might struggle with. In a particularly egregious distortion of Dweck’s ideas, some teachers have blamed students’ failures on the students’ own fixed mindsets; others have simply chided kids for insufficient effort. But as Dweck pointed out in a talk earlier this year, a failing student who has tried harder will feel even more inept if not shown better strategies.

Such misapprehensions not only turn Dweck’s message on its head but have opened her up to criticism for furthering ideas that are actually anathema to her. In a controversial Salon piece last year, Alfie Kohn, a firebrand of progressive education, accused Dweck of supporting an up-by-your-bootstraps agenda that puts all the onus on the student.

One of Dweck’s collaborators, Susan Mackie, dubbed the cluster of misunderstandings “false growth mindset.” Dweck says that once she heard about it, she saw examples everywhere. Some parents and teachers praise children for effort even when the child hasn’t exerted much effort at all—a distressing reversion to the self-esteem tactics Dweck has devoted her career to countering. Others have taken to hollow, misleading promises that “you can learn anything”—a phrase they might have picked up from Dweck admirers Bill Gates and Khan Academy founder Sal Khan, both of whom have used it to distill her message to tweet size.

Like the #growthmindset hashtag that gets tacked onto some of the hokiest truisms on social media, the term is bandied about to bolster so many notions that it has all but lost its meaning. “It’s like everybody feels they need to say they have a growth mindset,” Dweck says, even if they don’t walk the talk.

There’s also the all-too-human wish for a silver bullet. Dweck says the Los Angeles school system showed teachers her 10-minute TED talk—and sent them off to implement it. She’s seen similar problems with business institutions, who often underestimate the work that goes into understanding the growth mindset and putting it into practice. One large corporation was ready to pin its future on her ideas, but by inviting Dweck to give a talk to the company’s “high-potential employees,” they showed their obliviousness to one of Dweck’s basic tenets: that a person’s true potential is unknowable.

The dilution of the growth mindset concept risks more than Dweck’s reputation. “The danger is that the idea, which has solid research backing and has yielded in some cases spectacular results, will become discredited,” she says.

What’s happened to Dweck mirrors the experiences of some other psychologists whose research captured the imagination of the public. The “grit” concept developed by Angela Duckworth of the University of Pennsylvania has often been reduced to plain old perseverance, and Florida State professor Anders Ericsson’s research into deliberate practice continues to be equated with the bogus notion that you need 10,000 hours of practice to achieve mastery in any field.

“When any concept becomes popular, it can drift away from the original research,” Dweck says, “and it’s our job [as researchers] to do the work to bring it back.” That means not only clarifying the message but also doing further research. When Dweck’s book first came out, the scientists themselves had only a limited understanding of how to instill a growth mindset. Newer research is showing that it doesn’t get transmitted through words so much as through deeds, like probing for kids’ understanding and giving students a chance to revise their work. In one recent set of studies, graduate student Kyla Haimovitz worked with Dweck to investigate how parents’ mindsets about failure affect their children’s beliefs; they found that parents who see failure as debilitating tend to focus more on their children’s performance than on their learning—and that parental beliefs about failure foster a more fixed mindset in the children.

Somewhat surprisingly, Dweck has been suggesting that we should legitimize the fixed mindset instead of seeing it as the evil antithesis of the growth mindset: We are all, she says, a mixture of both beliefs. And rather than just proclaiming that we have a growth mindset, we ought to work to strengthen it. In Dweck’s freshman seminar, for example, she challenges students to do something “outrageously growth mindset.” One extremely shy freshman ran for dorm president; he not only survived the experience, he won—and felt emboldened to further stretch his social side.

Not every student sees such dramatic results, of course, and some even feel discouraged after the assignment. But, Dweck says, “I’ve never had an experience where the student wasn’t proud of what they did and what they learned from it.”

Marina Krakovsky, ’92, is the author of The Middleman Economy: How Brokers, Agents, Dealers, and Everyday Matchmakers Create Value and Profit.

This article written by Marina Krakovsky appeared in the November-December 2016 issue of Stanford magazine.