The Words That Bind (Discover)

“I can’t pay you a cent more,” Boris tells Sophie, who’s trying to sell him a car. But Sophie stands firm. “You’ll just have to match my price,” she tells him.

Around the corner, Ethan and Vickie are haggling over the price of her car. “I really can’t pay you any more,” Ethan says, but Vickie won’t budge, either. “The price is the price,” she says.

On the surface, these two exchanges might seem materially the same. But if you were to put them under a microscope, you would notice a subtle difference between them. Boris and Sophie’s verbal styles are similar to each other in some key ways; both use personal pronouns like you and I, for example. In contrast, Ethan and Vickie’s language styles are more divergent: While Ethan uses personal pronouns, Vickie uses none.

In isolation, such linguistic quirks are probably meaningless. But over the course of a conversation, they add up in telling ways, according to a new study led by Texas Tech University psychologist Molly Ireland. Though we’re seldom if ever aware of it, she argues, nuances of people’s language — such as their use of personal pronouns, articles or contractions, among many other linguistic choices — provide clues to their mental state or social status.

A small twist of language can signal friendliness or aloofness, deference or dominance. When two people are tuned into each other’s mental states, they tend to match each other’s language styles. And that engagement can spell doom in contentious situations like negotiations.

“It sounds counterintuitive because we think of similarity and synchrony as good for relationships,” Ireland says. And usually they are. “But of course matching another person’s mental state won’t bring two people closer together if both are thinking about how they can destroy each other.”

Leaky Language

Ireland’s insight stems from research she began as a doctoral student at the University of Texas at Austin, in the lab of psychologist James Pennebaker, who was studying how people’s written language relates to their psychological and physical health.

Because scanning people’s writing for specific kinds of words is labor-intensive, Pennebaker and colleagues automated the process. The language-analysis software they developed, called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC, pronounced “Luke”), contains a dictionary of thousands of words, sorted into dozens of categories — for example, words connoting anger, words pertaining to the body, or causal words such as “because.” The software parses any text file (including transcriptions of spoken language) and tallies the number of words that fall into particular categories.

Although Pennebaker’s program can examine any number of word categories, he discovered the most psychologically revealing results came from counting “function words” such as personal pronouns (like you and my), impersonal pronouns (like it and that), contractions (like can’t and they’ll) and articles (likethe and an). In one study, Pennebaker and a colleague used the software to compare pronoun use by two groups of poets: those who had killed themselves and those who had not. Suicidal poets used the pronoun “I” more often — perhaps a reflection of the excessive self-focus that’s common in depression.

The reason people’s use of pronouns and other function words provides such a window into the mind may stem from their connection to social behavior at a neural level, Pennebaker suggests. Studies of brain-damaged patients have shown that the same brain area responsible for processing such words — a region in the left frontal lobe known as Broca’s area — is also involved in social tasks, such as recognizing emotional expressions.

Some research indicates this area also contains mirror neurons, specialized cells that may be involved in imitation and empathy. People with severe damage to Broca’s area lose both their social skills and the ability to call up prepositions, pronouns and other function words. A person with such damage might say, for example, “Want … see … movie … week.”

The apparent connection between function words and social behavior spurred Pennebaker to dig deeper. He suspected the psychological importance of these little-noticed words extends beyond the individual mind; perhaps, he thought, they also play a role in personal relationships. He assumed that connection could only work in one way: that the more two people like each other, the more closely their language styles would match. But when he began analyzing actual conversations, he found no correlation. “It just bugged the hell out of me,” Pennebaker says. If two people are speaking “as though their heads are connected,” how could that not be a reflection of how well they like each other?

The answer came to him as he was listening to the car radio one day. He heard a snippet of dialogue from a play about a couple in the midst of breaking up and noticed they were using language almost identically. Musing as he drove, Pennebaker thought of the way angry drivers hurl matching F-bombs.

He realized he’d been thinking of language style matching in “completely the wrong way. It’s not about liking — it’s about engagement.” In other words, such synchrony reflects not how much the speakers like each other, but how much they’re paying attention to each other’s mental and emotional states. In one test of this idea, he and a colleague analyzed conversations on the Nixon-era Watergate tapes. On the tapes, they found, language style matching occurred about equally in intensely positive and intensely antagonistic conversations.

Ireland, working in Pennebaker’s lab, was fascinated by the notion of such “antagonistic style matching,” which she regarded as a form of behavioral mimicry. “You see it everywhere — human boxers or cats circling each other before a fight, people shouting similar accusations at the same volume and pitch,” she says. Yet in part because people rarely pick fights during brief interactions in laboratory settings, making antagonistic exchanges tricky to study, antagonistic style matching “is almost completely ignored in psychology.”

Too Attuned?

Ireland’s chance to examine how language styles play out in antagonistic interactions came in 2008, when psychologist Marlone Henderson joined the UT psychology department. Henderson was studying negotiation, with a twist: Participants negotiated through instant messaging rather than face-to-face. Transcripts from such interactions, Ireland realized, were ideally suited to research on the dynamics of language styles because there is no body language or tone of voice to muddy the waters.

Ireland and Henderson decided to collaborate, mining the trove of data Henderson had already collected. In one experiment, Henderson had 128 college students take on the role of co-workers, giving them 20 minutes to negotiate travel plans for an upcoming business trip. To amp up the conflict, Henderson rigged the situation so participants’ negotiation goals were opposite those of their faux co-workers: If one wanted to fly, the other preferred to drive. If one sought a posh hotel, the other wanted cheaper digs.

When Ireland got her hands on Henderson’s data, she found just what she predicted: The more negotiators used similar styles of language, matching each other pronoun for pronoun, article for article, the more likely they were to reach an impasse. It wasn’t the number of function words people used that mattered; it was how closely their particular styles of using them matched.

Ireland regarded the data as strong support for Pennebaker’s notion that language style matching reflects psychological engagement; to her, it stood to reason that getting too psychologically attuned during a contentious interaction was bad news.

Then Ireland and Henderson hit an impasse of their own. Three psychology journals rejected their study because reviewers were unconvinced: Perhaps, some reviewers suggested, language style matching was simply a matter of liking, as Pennebaker had initially assumed. That is, negotiators whose language styles most closely matched may have simply liked each other so well that they wasted their 20 minutes on friendly chit-chat and never got around to discussing their travel plans.

Analyzing questionnaires participants filled out after finishing the study, Ireland could see that wasn’t the case: The pairs whose language styles matched most closely did not particularly like each other. But it was true that Ireland and Henderson’s data couldn’t conclusively demonstrate that more similar language styles reflected emotional engagement — or that such heightened engagement caused negotiations to fail.

Frustrated and busy with other projects, Ireland put the study aside and moved on to other research. Studying more convivial social situations, she found an opposite pattern of effects from what she’d found in the negotiation study. In a study of speed-daters, she found that couples whose language styles most closely matched were more likely to pair off than those whose language differed. And dating couples whose instant-messaging streams showed matching language styles were much more likely to remain together months later.

It wasn’t until 2011 that Ireland came to fully understand the results of the negotiations study she had shelved. On a whim, while creating new dictionaries to expand the LIWC software’s standard lexicon, she decided to create a list of words relating specifically to the task of negotiating travel, which participants in the earlier study had faced: words like “car,” “hotel” and “train.” Then she measured the frequency of these words in the transcripts from her negotiation study.

Suddenly, everything made sense. Negotiators who used more words related to the task at hand were more likely to reach a negotiated agreement — and the more they used such words, the less their language styles matched. In other words, time spent focusing on the negotiation goal was time not spent tuning in to the other person’s mental state.

Ireland’s results, which have been accepted for publication in Negotiations and Conflict Management Research, might appear to contradict her findings with dating couples, where greater language style matching was associated with better outcomes. But both sets of results, she says, support the core idea that Pennebaker proposed: that the act of matching another person’s language style reflects and amplifies attention to social cues, whether positive or negative.

In competitive or hostile situations, that’s a recipe for failure; better to focus on the task at hand. In more cooperative conversations, though, matching can help ease the interaction. And on a date … well, who gets gussied up to go out, only to talk about tasks?

The notion that the subtleties of people’s language choices carry such freight holds tremendous practical potential, Ireland says. She envisions companies one day using a chat-notification system to alert managers to simmering interpersonal problems in their departments; or married couples using similar techniques to see how well they’re paying attention to each other.

She marvels at the capacity of language-analysis tools to peer into people’s minds. “If you read these transcripts, they seem identical,” Ireland says. When you count the words, though, “a whole new world of psychological nuance opens up.”

COPYRIGHT 2013 © Marina Krakovsky. All Rights Reserved.

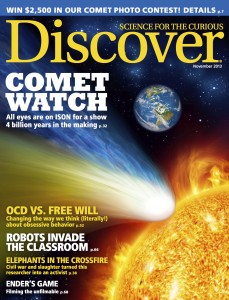

This article written by Marina Krakovsky appeared in the November 2013 issue of Discover magazine.